This story comes from my grandparents: my grandma better known to my family as “Baba” and my grandpa as “Deda.” Baba and Deda translate to grandma and grandpa in english. My grandparents emigrated from Soviet-Ukraine in 1979 once the Soviet Union began to allow Jewish families to immigrate to the United States. Deda got these pair of loafers along the journey in Italy, and they have been with him through many experiences and seen many days of work.

Before they left their city, Lviv, Baba managed 17 factories that processed gravel, sand, pipes and other construction materials. She was one of the top managers at the factory. Deda was the superintendent at one of the only food factories in their area; a bigger food warehouse so they had reliable access to food which was an advantage in that time. They could pay for healthcare and barter with goods. When they ended up emigrating, people thought they were crazy because it was a good set-up. But they had good reason.

“My friend at work told me her son was fighting with the Soviet army in Afghanistan. A coffin just arrived, and it was her only son. I didn’t want my sons to be sent. Alex was turning 18 and would be forced to go,” Baba said. “My friend told me: ‘You’re Jewish. Cry, walk, run, because they are going to take Alex and he will be in a coffin next, and your other son Vadik too. Get out of the country, run!”

To be allowed out of Lviv, first they had to immigrate to Israel and claim they had family there to receive them. Finally, they received permission and fled to avoid Alex and Vladik being sent to their deaths.

“All eleven in our family left. We immigrated to Austria after Israel. Once we left Lviv, we were enemies,” said Baba. “Alex and Vladik were thankful. Marianna, your mother was so young, just four years old, and cried for home. It was hard to explain why we had to go. Ukraine was just one of 17 countries that was under Soviet control and we had to leave to protect our children.”

When they were leaving, they almost didn’t make it. It’s Jewish tradition to sew a penny into a comforter as a wedding gift. Deda recalls, “At a checkpoint, Soviet officials held us back. They cut the down comforter open in front of everyone because when they were scanning they thought we were smuggling something out of the country. I was holding Marianna watching them, covered in feathers. The train started to leave as they finally cleared us. I began to run, and passed Marianna through the window to Baba, and I made it on just in time.”

The train went to Vienna, Austria. They were given an apartment for two weeks via a Jewish sponsor family. They were helping Jewish people leave the Soviet Union due to religious persecution.

“We had to leave. Nobody in Ukraine liked Jewish people. Antisemitism was alive and well,” said Baba.

After Austria, they had to take another train to Rome. The whole train car was Jewish people fleeing. My mother, Marianna, was screaming and crying still; she just wanted to go home.

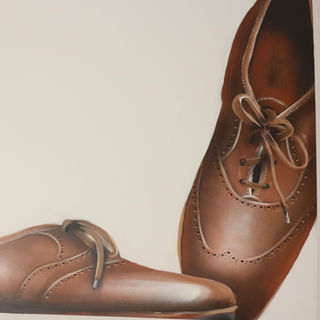

They were placed in another temporary apartment, a brief reprieve on the sea from the grueling journey. They didn’t know where to go after Italy. Everyone said to go to back to Israel, but they had family in the United States. Deda got his loafers in Rome, so he would have shoes to work in.

After Rome, all immigrants had to be vaccinated and checked, but Deda was sick. They were scared they wouldn’t be able to leave Europe. They were trying to get to Baba’s cousin who had fled the year prior, and told them of Jewish communities in New York, Chicago, and Minneapolis. After the Holocaust, many Jewish familes wanted to leave Europe and start anew in the United States.

Baba and Deda made arrangements to get the entire family to the United States. They were initially going to go to Chicago, but Deda’s brother was in Minneapolis, so they ended up going there. I asked them what it was like when they arrived.

“The Jewish Community Center set up apartments for immigrants. We got three apartments for us eleven for $50 a week,” said Deda. “A week after we got here, an FBI agent came to our door with an interpreter because Baba ran 17 plants in Lviv, so they thought we were spies. They asked for documents to confirm she was in industrial construction.”

After that, they began to settle into life in Minnesota. “We took English classes for two months,” said Baba. “My first job was customer service at a bank, just two weeks after English classes began. The first two months of my job, I didn’t understand a single thing at the bank, but I did know Economics from my degree, so I was able to process the deposit slips. A lady I worked with took me under her wing, and would answer phones for me so no one would catch on, and I could continue to support my family. Finally, my boss realized I didn’t know English well enough and they had to let me go.”

My grandparents told me how they slowly but surely built a life for themselves and their three children in Minnesota. Deda explained how his loafers from Italy saw him through endless shifts as a janitor. “These shoes have been through a lot with me. Across oceans. I’m proud of who I am and where I come from. And I’m grateful to have come to Minnesota with my family.”